Rewrite #2: Tools of the Trade + Character Names

Rewriting a novel is a big job. What tools should you use? Plus: how do we choose character names? Enjoy this week's edition of (Re:)write!

After my previous issue came out, my wife asked me what dungeon I took those photographs in. I hadn’t realized that my writing studio, a cozy little room on the second floor of our little suburban home, could be described as a dungeon. She felt the dinginess of the photos — the browning paper and the so-ugly-it’s-cool rug — were not the sort of foot that we’d like to put forward for my global audience.

Personally, though, I felt like they screamed, “It’s not working (yet).” I’m no photographer, that’s clear. I also didn’t care too much about the quality of the photographs, what I wanted were the ideas: here’s a manuscript on the floor, here’s the first couple of pages. Beyond that, I’m a writer and don’t really care. I was using my iPhone and the early morning light through the window to take those photos, and that’s good enough for me.

But, while I might look at photos and scans on this blog and think, “That’s good enough,” I can’t really do that for the writing. Writing, after all, is my art: it’s my practice. Therefore, in this issue of (Re:)write, I want to think about a few things that are indispensable to my practice as a writer and to show you that practice as I get to work on my rewrite of the first chapter of The Brief and Horrible Resurrection of Lorraine Barth.

Tools of the Trade

Let’s talk about what we really mean when we say “writing.” I’m not talking about simply putting words together to form phrases and sentences and such. If I’m sitting in a meeting, for example, I might take notes. The act is very similar: words → phrases → clauses → sentences → paragraphs. I’m using written language to encode ideas on a page (whether physical or digital). However, note-taking and writing aren’t the same thing.

Note-taking, typically, means creating notes for my own personal use later on. It’s rare, though not unheard of, for me to publish my notes. These notes are intended to document an event or some kind of thinking so that I can process it later on. Consequently, my notes are totally idiosyncratic. If you were to sit in a meeting with me and then read my unvarnished notes afterward, a few things would likely happen.

- You’d find yourself a little lost, as I tend to only take notes on the stuff that’s important to me. I’m self-centered like that.

- You might not be able to make out what I’m talking about anyway because I often take notes in short, bullet-style phrases.

- You’d probably be offended because I tend to write a bunch of snarky, sarcastic notes about whatever is going on. It’s how I keep myself entertained.

The notes are for me. I’m the audience. An audience of one. Me.

With writing, however, I’m typically trying to communicate ideas, rather than simply documenting what’s going on. I’m looking to publish the ideas. I’m producing this for an audience. Writing, then, is much more careful, much more polished, much more, dare I say, contrived…but in a good way!

We can think of writing as having two basic processes: input and output. Input is the actual creation, using letters to form words to form phrases, etc. Output is about the publication of those words for others to read. Different tools are better for different things based on what input mode makes sense and what output mode makes sense.

Let’s look at some different tools.

Good ol’ Pen and Paper

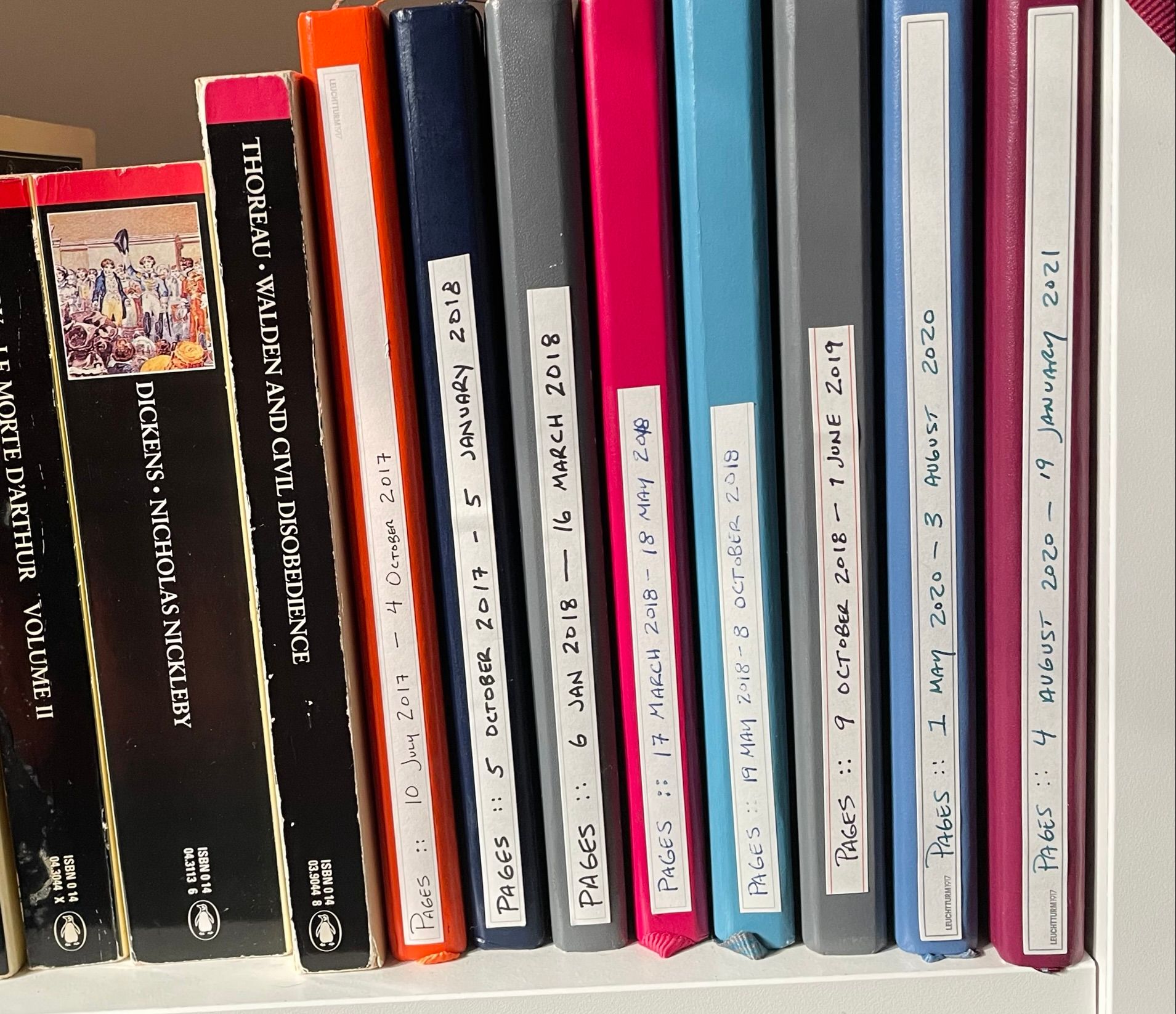

I wrote much of Lorraine longhand in notebooks like the ones pictured below.

In a digital age where you can type so much faster than handwrite, you might wonder why.

Well…because I felt like it!

Also, I’d gotten into fountain pens as a thing that I collect. I’m always looking for that latest thing to collect, that thing that will make me feel fancy. It’s my own form of consumerism. Over the years, I’ve collected comic books, fountain pens, typewriters, baseball cards, and unopened medical bills. Each collection tells a little piece of my story, doesn’t it?

Writing longhand, however, does have some advantages.

First, if you choose to write with pen and paper, you are saying to the world, “I’m a Luddite.” If the medium is the message, then the artist is her tools, right? Why not make a statement with the tools you use? Moreover, because you cannot store your handwritten pages in the cloud, you’re really throwing caution to the wind here. If your house catches fire, floods, falls over spontaneously, well, then you’re shit-outta-luck, my friend. Nothing says “Art is About This Moment” like willfully choosing to forego the conveniences of cloud storage.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, writing longhand tends to mean that you’re going to put off the editing process until later. If you’re the kind of person who really struggles to keep things moving because you’re constantly tinkering with what came before, then this could be a good tool for you. In fact, this is precisely why I switched to writing longhand for a while. It’s damned annoying to edit on the fly, so you just keep the thing moving forward.

Third, if you’re like me, then you start most mornings with a standard writing practice like Julia Cameron’s “morning pages.” Sometimes, as I’m writing morning pages, I start getting ideas. The best thing to do is get them down. As a rule, during morning pages, I don’t look at anything else: no books, no screens, nothing. I’ve got my pen and my paper. Start writing.

Finally, one of the great things about pen and paper is that you’ll find yourself going through a first edit when you make the transfer from the page to the processor. When I moved those scenes or snippets from my journal to my word processor, I didn’t transcribe them exactly as they were. Instead, I edited them along the way. This meant that by the time I had compiled a draft of my novel, I’d also edited a bunch of it as I transcribed it. In my view, it makes things better.

The downsides to writing by longhand are obvious, but when it comes to rewriting, even more so. I can only think of one process for rewriting in longhand and, as I think about it, it sounds incredibly annoying. That being said, who knows, maybe it’ll work for you! Here’s what that process could look like:

- Read the scene you’re working on.

- Put the scene away and rewrite it longhand.

- Transcribe (and edit-as-you-go) your handwritten material back into your word processor.

What might be advantageous about this? Well, you’d get the benefits of writing longhand (as mentioned above), but you’d also probably reduce your scene into its best, most essential bits. Think about it this way: If you were going to rewrite a scene without the benefit of reading it while you rewrote it, then you’d probably only reproduce the best bits. This method could do that. You’re likely to compress your composition and maybe discover some new ideas, but you’ll still have the best of what came before…

…maybe.

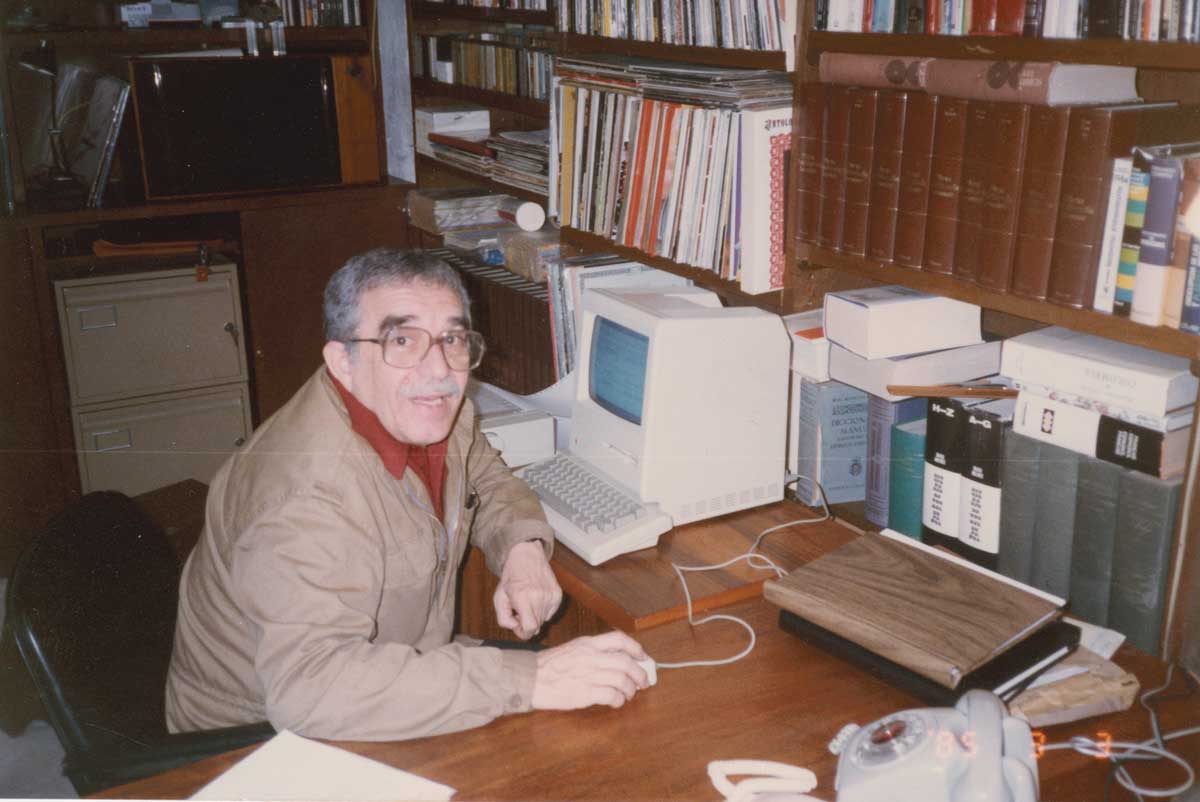

As for me, well, I think word processing is probably the way to go for a rewrite project. I’m reminded of Gabriel García Márquez’s excitement about his Macs. When word processing became available to him, he reportedly loved that he could write and rewrite and rewrite some more.

Apps: Scrivener and Ulysses

Whether you choose to write by hand or not, you’re eventually gonna need to get these words into an app of some kind because you’re now living in the 21st century, and this is something that 21st-century people do.

(NOTE: Should the internet survive cataclysmic climate change and should you no longer be living in the 21st century, kindly update this to whatever century you’re now living in. Thanks!)

I’ve tried all kinds of word processors, but, at the end of the day, I’ve only found two writing machines on my computer (and phone) that work for me:

The internet is full of reviews of these things. You can Google around and find comparisons and such. Many times, these comparisons are geared toward finding the app that works best for you, but that’s not my approach. A good handyman has more than one screwdriver, more than one hammer, more than one wrench. (So, I’m told…I’m not very handy myself.) You’ve got to use the right tool for the job. Writing, like any other job, then, requires the right tools. Unless you’re constantly writing the same kind of thing (and in the same location on the same device), then you might need more than one tool.

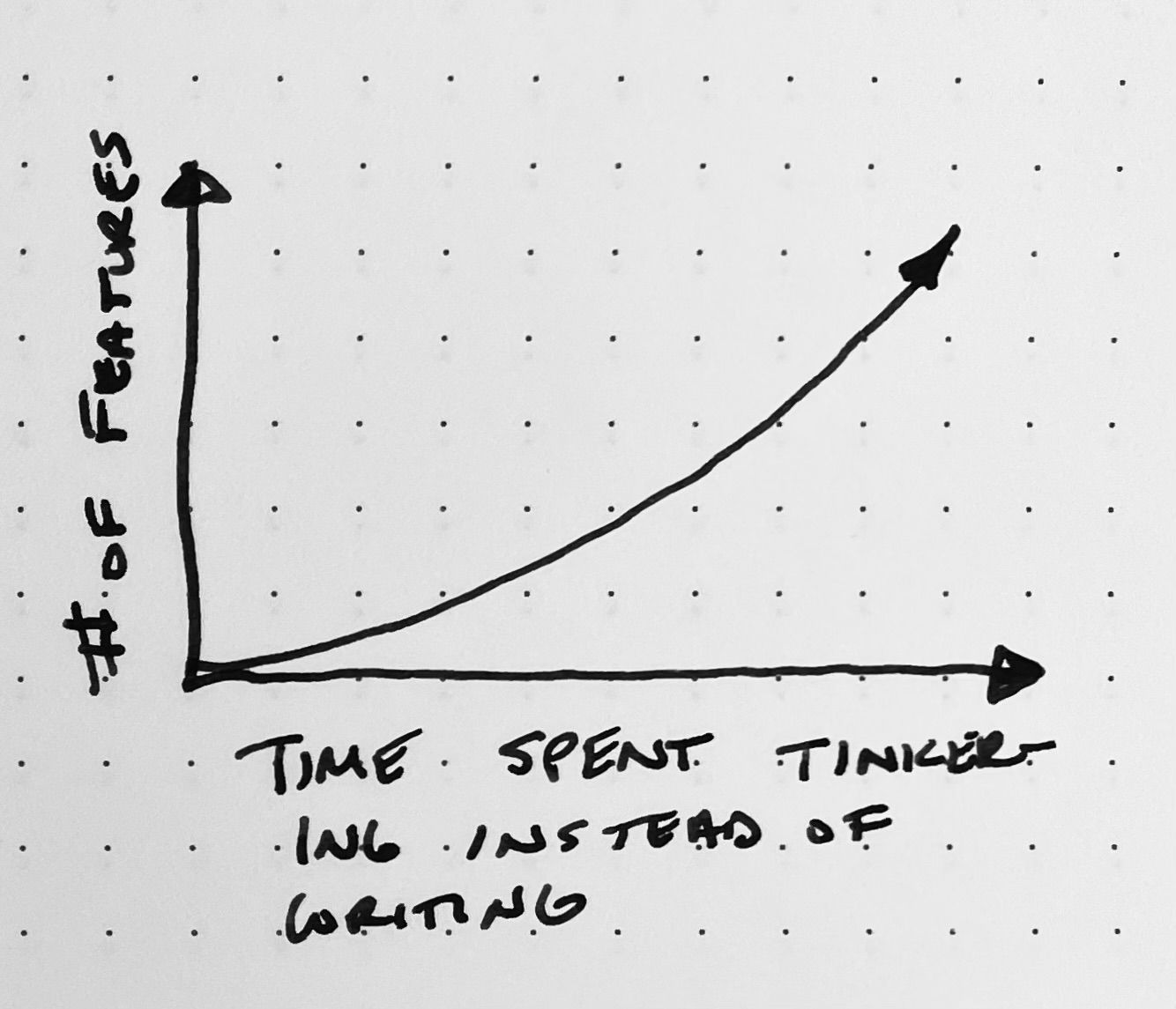

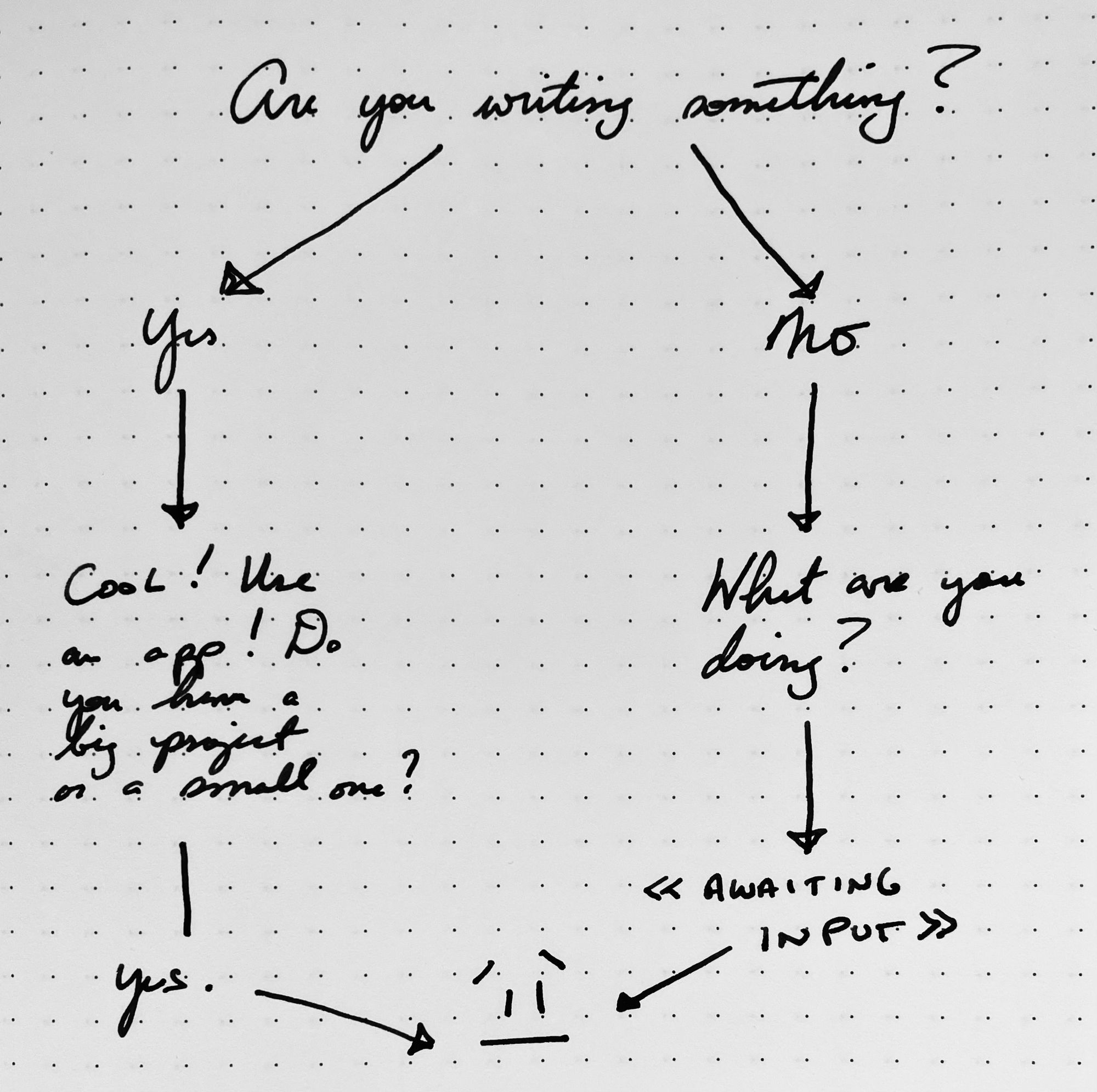

For your benefit, I’ve drawn a graph and a flowchart to help you think about when to use which tool:

I switch back and forth constantly. I love them both. As we go through this rewrite, I’ll highlight some different ways to use these tools to your benefit (both in drafting and in rewriting), but my general advice right now is this:

- Is your project lengthy and likely to be output in a very specific format (e.g., a standard manuscript form for a publisher)? Then use Scrivener.

- Is your project short and likely to be published on the web (e.g., via a CMS like Ghost or WordPress)? Use Ulysses.

I know someone is going to come forward and say, “I love writing my blog with Scrivener!” Likewise, someone else will say, “I’ve written three novels with Ulysses!” More power to you! You’ve got to do what works for you. Choose the tool (or tools) that you need for the job.

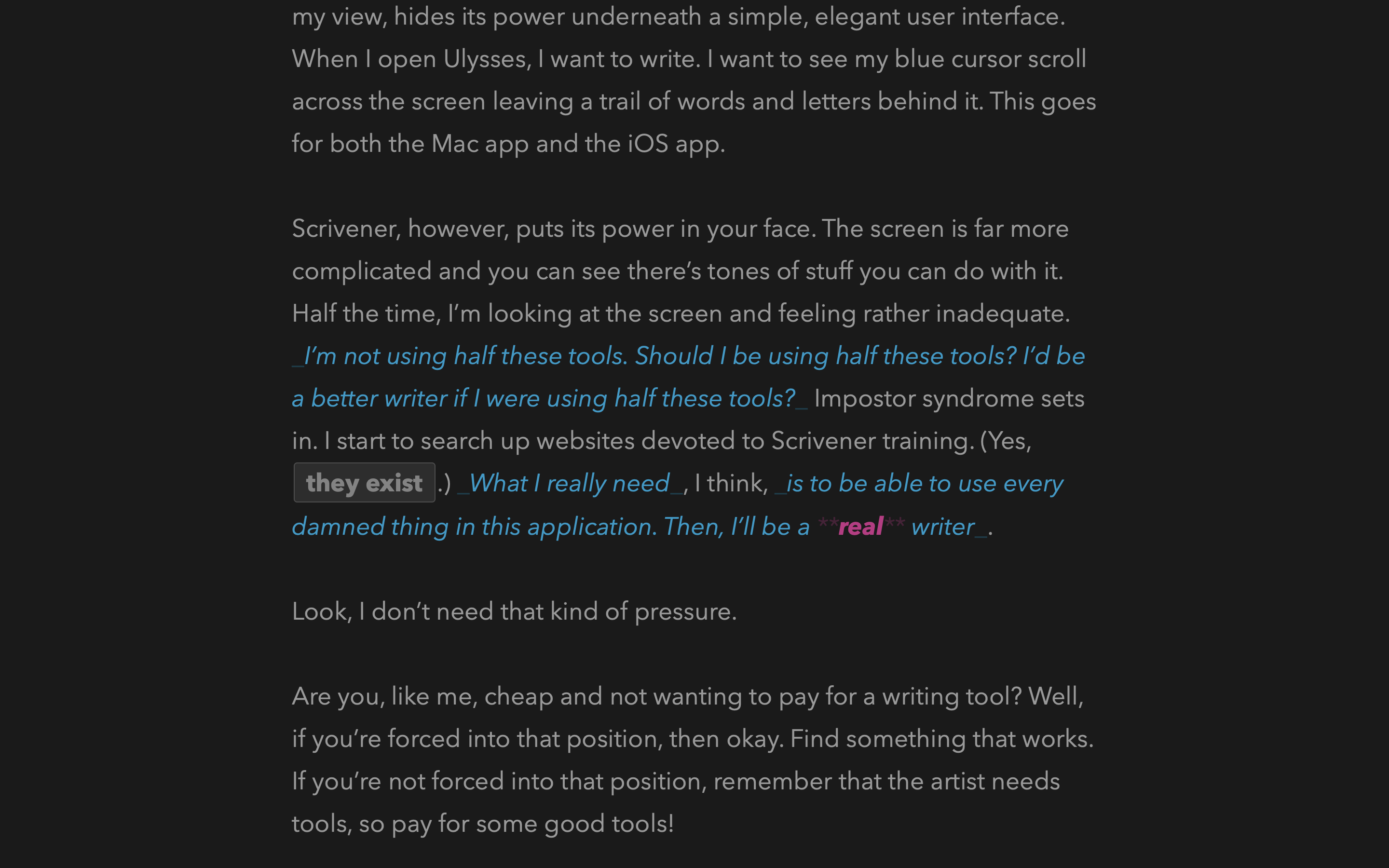

For me, Scrivener and Ulysses are both powerful tools. Ulysses, in my view, hides its power underneath a simple, elegant user interface. When I open Ulysses, I want to write. I want to see my blue cursor scroll across the screen, leaving a trail of words and letters behind it. This goes for both the Mac app and the iOS app.

Scrivener, however, puts its power in your face. The screen is far more complicated, and you just know there’s more you could be doing with it. Half the time, I’m looking at the screen and feeling rather inadequate. I’m not using half of these tools. Should I be using half these tools? I’d be a better writer if I were using half these tools! Impostor syndrome sets in. I start to search up websites devoted to Scrivener training. (Yes, they exist.) What I really need, I think, is to be able to use every damned thing in this application. Then, I’ll be a real writer.

Look, I don’t need that kind of pressure. Impostor syndrome is not helpful for my writing practice.

(By the way, Scrivener has an excellent “Full-Screen Composition Mode” that blocks all of this out. I use it all the time. Still, there’s a piece of me that feels like all those features are lurking underneath…)

If you don’t want to pay for Scrivener (a one-time thing) or Ulysses (a subscription), there are other options. Find something that works. But remember that the artist needs tools, so get some good tools…even if you have to pay for them!

A Note on Microsoft Word

In your search for writing tools, you might be tempted to use Microsoft Word.

No. Just don’t.

Moving on…

Rewriting Lorraine

My work on Lorraine this week has progressed nicely. I’m pretty shocked by that. I’m sure my fortunes will turn, but I’m going to ride this wave as long as I can.

This week, I’ve spent a bunch of time setting up my rewrite (more on that next week) and reworking the opening (more on that in a couple of weeks). This has forced me to reckon with two different voices and styles and a restructuring of the narrative. As I start to flesh these out, I’ll be writing about them more here. After all, I want you to see what I’m doing and why!

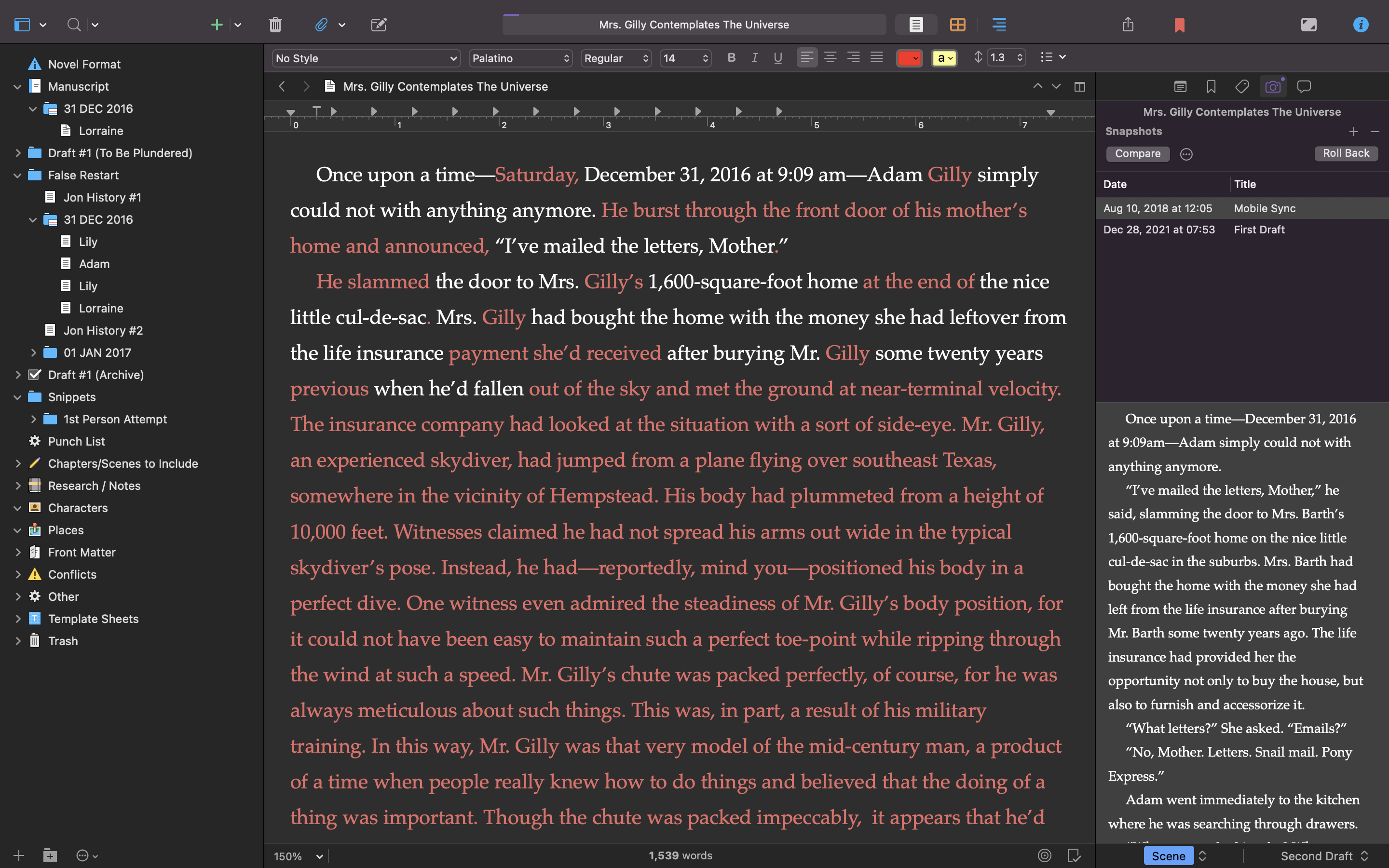

I’ve also chosen my tools for this project:

- For the rewrite of the manuscript, I’m using Scrivener. It’s got too many features (that I know how to use or want to discover) that are just too darned helpful.

- For writing these newsletters, however, I’m using Ulysses. It’s just perfect for it (and allows me to write in Markdown…which I love and will someday explain why). Combined with Ghost, it’s a great combination!

- Lastly, a tool that you might not think about, a task manager: Things 3. I’ll spend some time talking about how Things figures into my writing process. Stay tuned for all of that!

For today, though, I want to focus on character names. I’m working through a foundational change that has a ripple effect throughout the novel.

Rethinking Character Names

In the last issue, I mentioned that I’d like to change these names. I’m gonna be honest with you: I lied a little bit. In that issue, I said that I didn’t know why I named the characters the way I did, but that’s not entirely true. For my three mains — Adam, Lily, and Lorraine — I had some reasons for using those first names.

Before we get into all of that, let’s think about why we name characters the way we do. The first time I remember being aware of the importance of a character’s name was when I read Stephen King’s The Green Mile. I was in eighth grade at the time, deeply into Stephen King, and utterly drawn in by the serial novel format. I would walk down to the convenience store near my house. This little Stop ’n Go sat next to a liquor store and a copy shop. Other than the Pizza Hut a block or so down, it was the only commercial property I had access to by foot. Fortunately, they sold not only candy and Cokes (as we call them down in Texas), but they also had a magazine rack that included comic books and some popular books. I walked down to the Stop ’n Go at the end of each month in the spring and summer of 1996 to get the latest installment in the series.

Well, that was quite a trip down memory lane.

Anyway, one of the main characters in The Green Mile is a prisoner named “John Coffey.” While The Green Mile is a good tale — worthy of much of Stephen King’s page-turning output — it’s not as well known as some of his other work, so I don’t want to spoil it. Therefore, I’ll just say this about John Coffey: his initials are “J.C.” and he certainly seems to be written in the mold of good ol’ Jesus of Nazareth.

King hides Coffey’s messianic qualities, barely, by obscuring the name. He could’ve given the character a name like “Jesús Cristianos” or “Messiah Jones,” but he at least made his readers work for it a little bit. He didn’t do what the writers of Top Gun did and hit us over the head with a gigantic sledgehammer. Oh really, the character named “Maverick” is a non-conforming individualist? “Iceman” is calm, cool, and collected, even under pressure? The hell you say!!?!?!

Listen, I’m not saying we need to totally obscure our meaning behind symbols. I’m not T.S. Eliot. I want you to read and understand what I’m writing, but I also want to slip in a few little Easter eggs that might delight readers who are really paying attention.

In addition to creating some kind of symbolic resonance, we can also name our characters based on who they are as people. Names, after all, have meaning to us. A character unironically called “Biff” is going to be a tough guy. We communicate a lot to the reader by choosing such a name. We risk, however, falling into stereotypes. Biff is a tough guy. Veronica is sexy. Eugene is smart.

You want to avoid that.

Having written all this, I’m coming to realize just how difficult naming characters can be. We’re looking for balance here: something with symbolic resonance, something that’s not too obvious or stereotyped, but something that’s gonna help your reader a bit.

Colson Whitehead’s most recent novel, Harlem Shuffle, is an interesting lesson in this. The novel is a 1960s crime drama set in Harlem. It’s littered with characters like “Miami Joe” whose names tell us exactly who they are. At the same time, you have your main character — Ray Carney — whose last name might (please note the italics there) indicate that he’s a kind of circus impresario trying to hold things together: a “carney.” Then, there’s his father’s friend Pepper, a bruiser whose name sounds ironically sweet while also indicating the way he might pepper his victims with punches or bullets.

Alright, so how do I go about naming characters in my novel. We’ve got three primary characters in the opening section of the novel:

- Lorraine Barth — a fifty-ish widow

- Adam Barth — her adult son who has moved back in

- Lily Sommers — Adam’s down-on-her-luck girlfriend

For Adam and Lily, I wanted Judeo-Christian connections. Adam, of course, was the first human created in the Book of Genesis. He’s the first man! A reader can make that association, then read the first section, and start to think about what I might be trying to say about manhood/masculinity with that choice. Then, as the novel progresses and changes, those ideas of masculinity might be bothered, bent, or even broken.

Lily could be taken as the flower — often symbolic of the Virgin Mary, by the way — or a shortened form of “Lilith,” that wonderful she-demon of ancient Hebraic lore. Is Lily the ultimate picture of sacrifice, like Mary, or is she some kind of temptress who keeps other characters from making good decisions and becoming their best selves? Virgin or villain? The reader gets to decide.

While Adam and Lily were intentionally chosen for their religious connections, Lorraine is a bit different. I don’t really have a good explanation for her name, to be honest. I’ve just always thought it was a great name. I also associate it with Lea Thompson because I had a boyhood crush on Lorraine Baines from Back to the Future when I was a kid. (Who didn’t?)

Does the Lea Thompson connection make any sense here? Not at all, but it’s there for me, and I’m good with that.

At this point, nothing is going to change with these characters' first names. In fact, the more I think about them, the more I like them. Likewise, nothing will change for Lily Sommers at all. Two reasons for this:

- I haven’t gotten to the part of the novel where she’s introduced. (That’s the beginning of chapter two in the initial draft.)

- I like the sound of it! “Lily Sommers” rolls off the tongue, I think.

For Adam and Lorraine, however, I just can’t get on board with this last name: Barth. I don’t know why I chose it. Perhaps it came to me as some weird reference to theologian Karl Barth (typically pronounced “bart”). Maybe it’s because the softer “th” sound made “Barth” sound a bit like “barf.” Who knows?

At any rate, I’m not into this last name. As I worked, sentence-by-sentence, through the opening scene, I tried out different last names for Adam and Lorraine. For the moment, I’ve settled on “Gilly.”

This yields a new trio at the heart of the story:

- Lorraine Gilly

- Adam Gilly

- Lily Sommers

Are there future opportunities to rhyme “Gilly” and “Lily”? Yes. Am I going to play with that? Yes. Am I set in stone? No.

This last question is important. This is writing. Nothing is set in stone until it’s published. You can reserve the right to change anything at any time. Enjoy that privilege! I’m not totally committed to this name change. I can change them again. With find-and-replace, it’s easy!

That's all for this week. I plan to be back next Friday with a few updates and some know-how:

- The Setup: How have I set up Scrivener for the rewrite? What does my file structure look like? What tools am I using?

- The Update: What's going on with the actual text? How's the rewrite going?

I'm sure some other stuff will pop up along the way. If you have ideas or questions, please reach out to me. There are two easy ways to do that:

- Find me on Twitter and send me a message: @sbhebert.

- If you're a subscriber, then you can log into your account on the website, and find the "Contact Support" button there. I'm "Support"!!! You'll be able to email me with that.

If you're reading this and haven't subscribed yet, please consider doing so! You'll get inwy "(Re:)write" (and more) delivered right to your inbox. If you are a subscriber and you find inwy is bringing value to your practice, consider becoming a donor. What do you have to lose? Well...a few bucks, I suppose. :)